How Four Scientists Created Gatorade and Became Billionaires

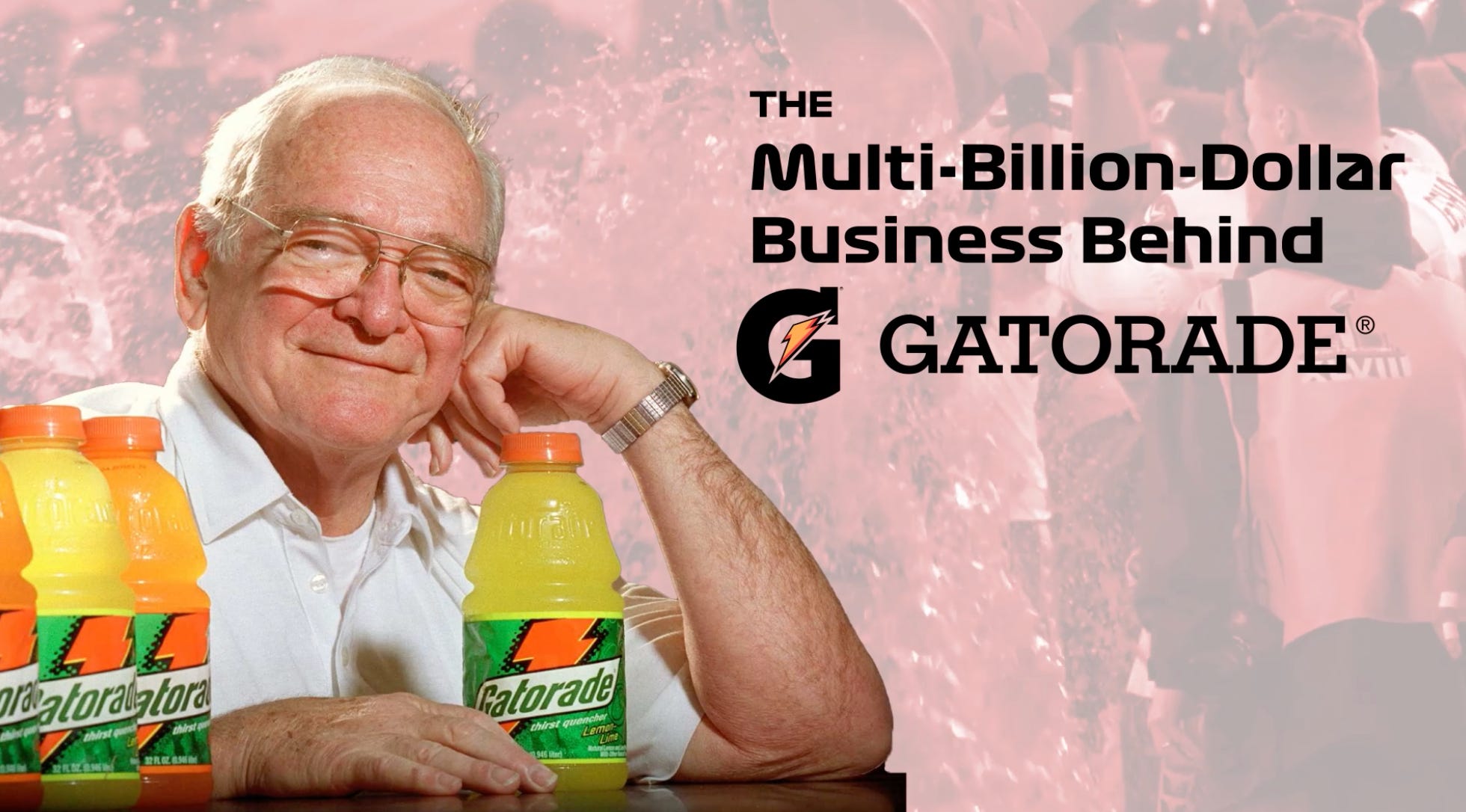

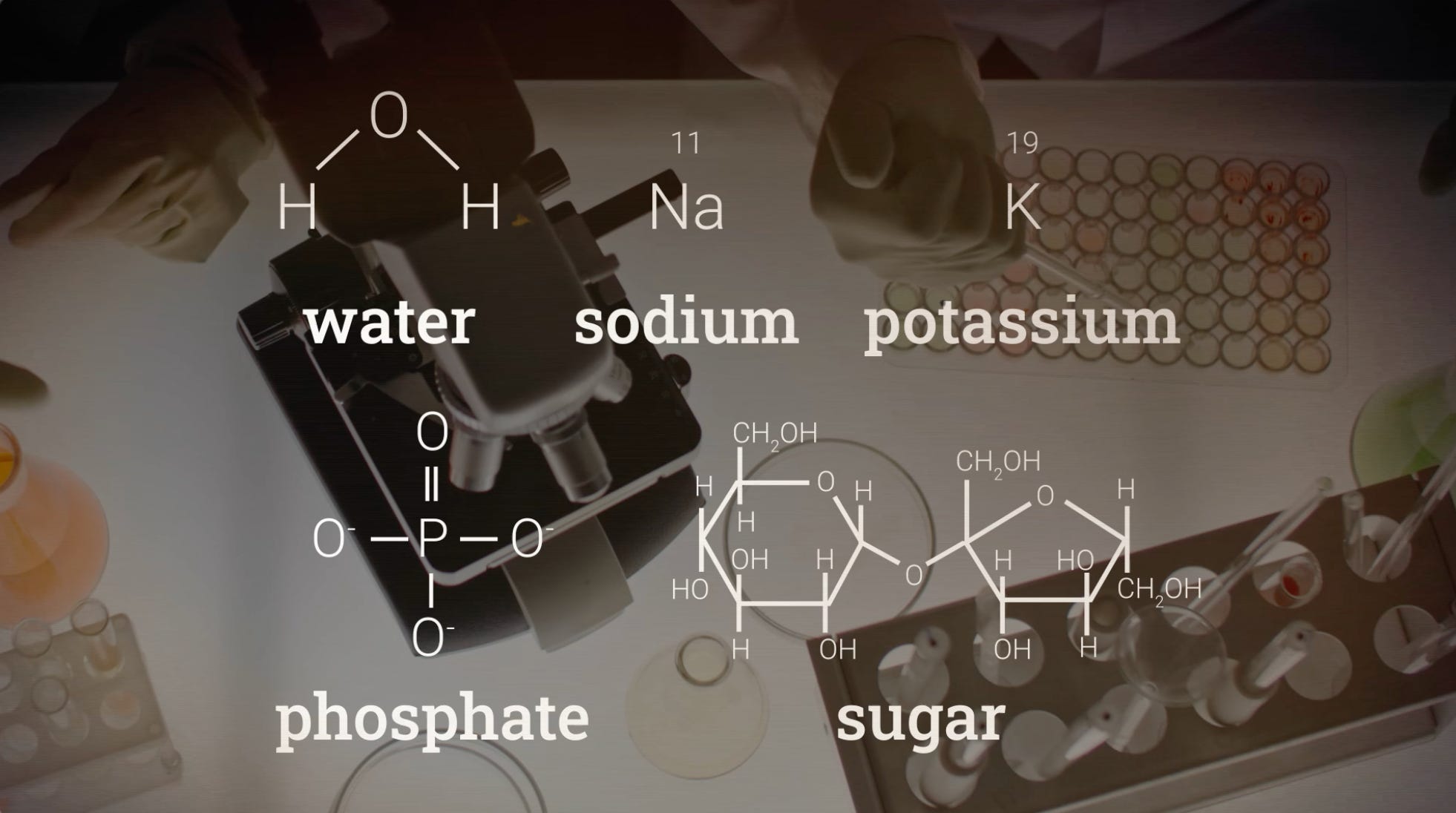

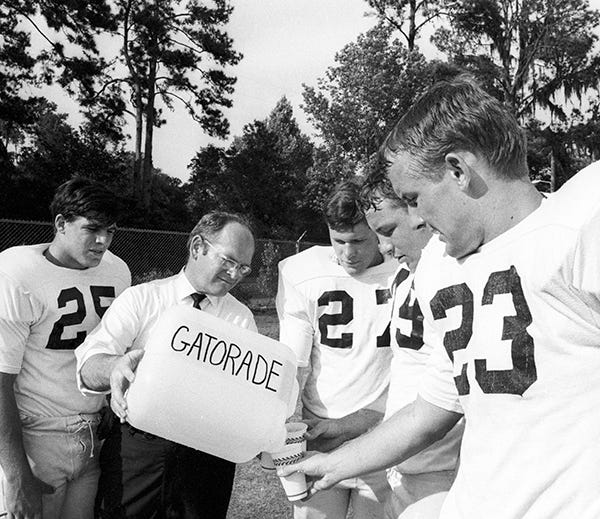

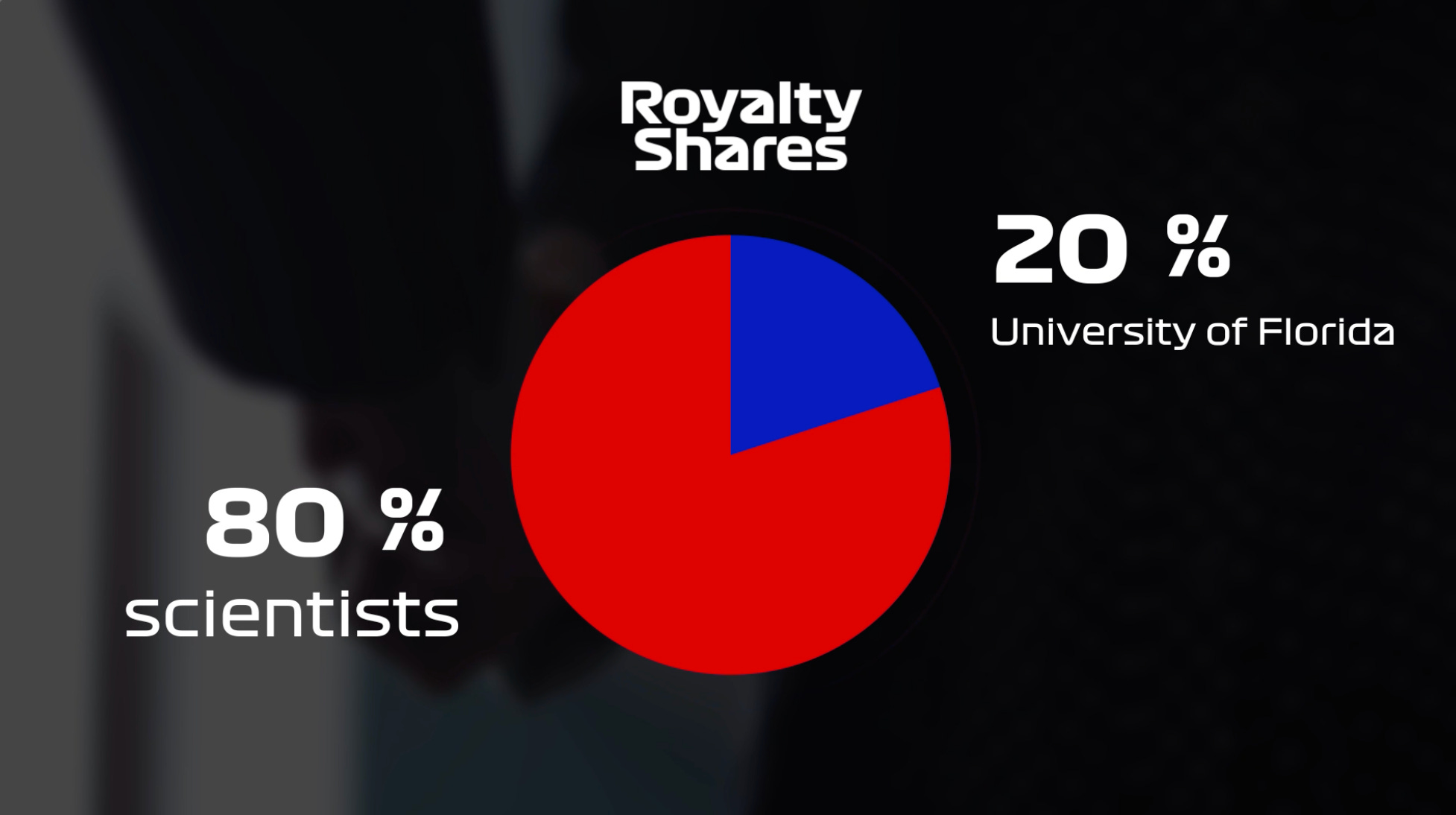

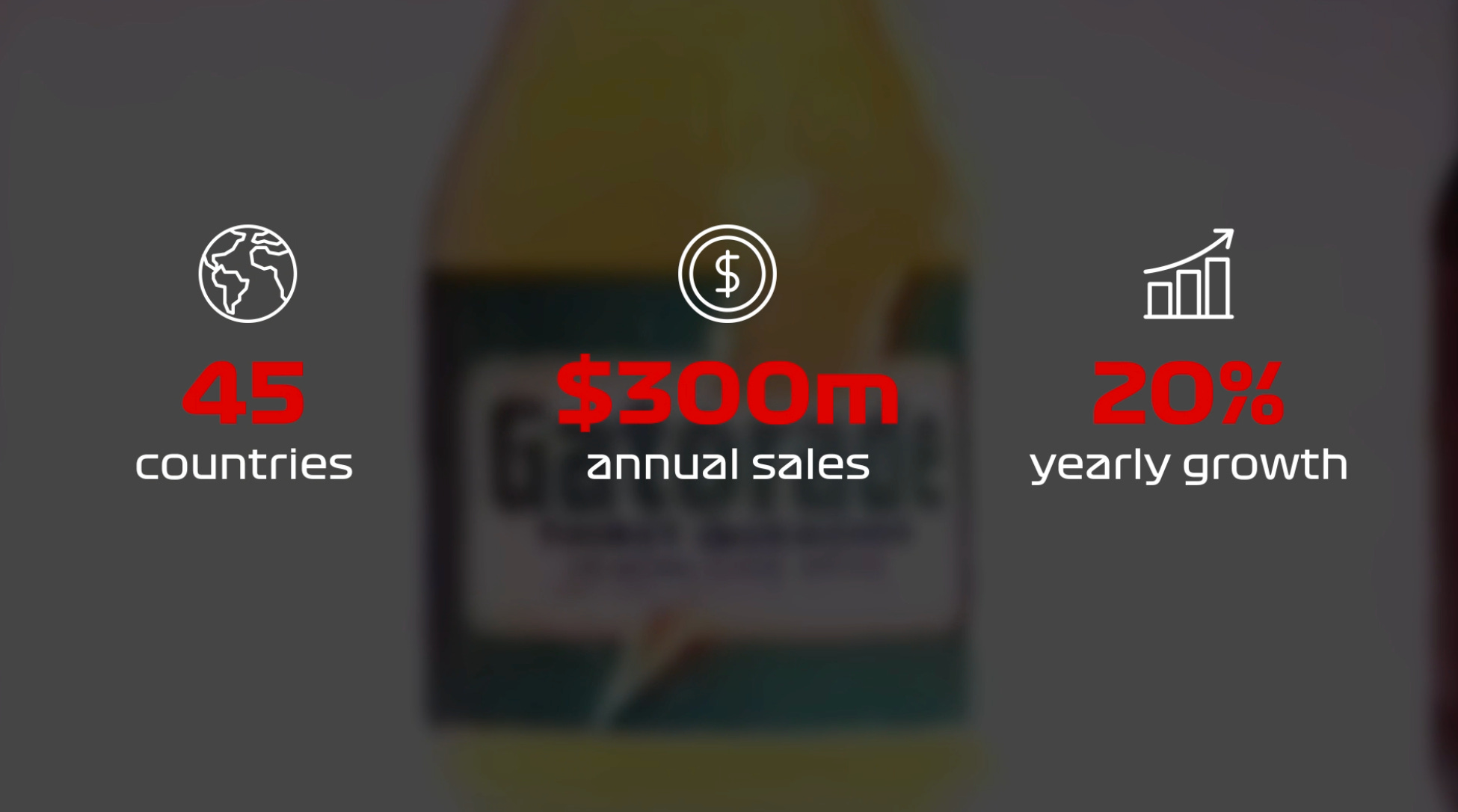

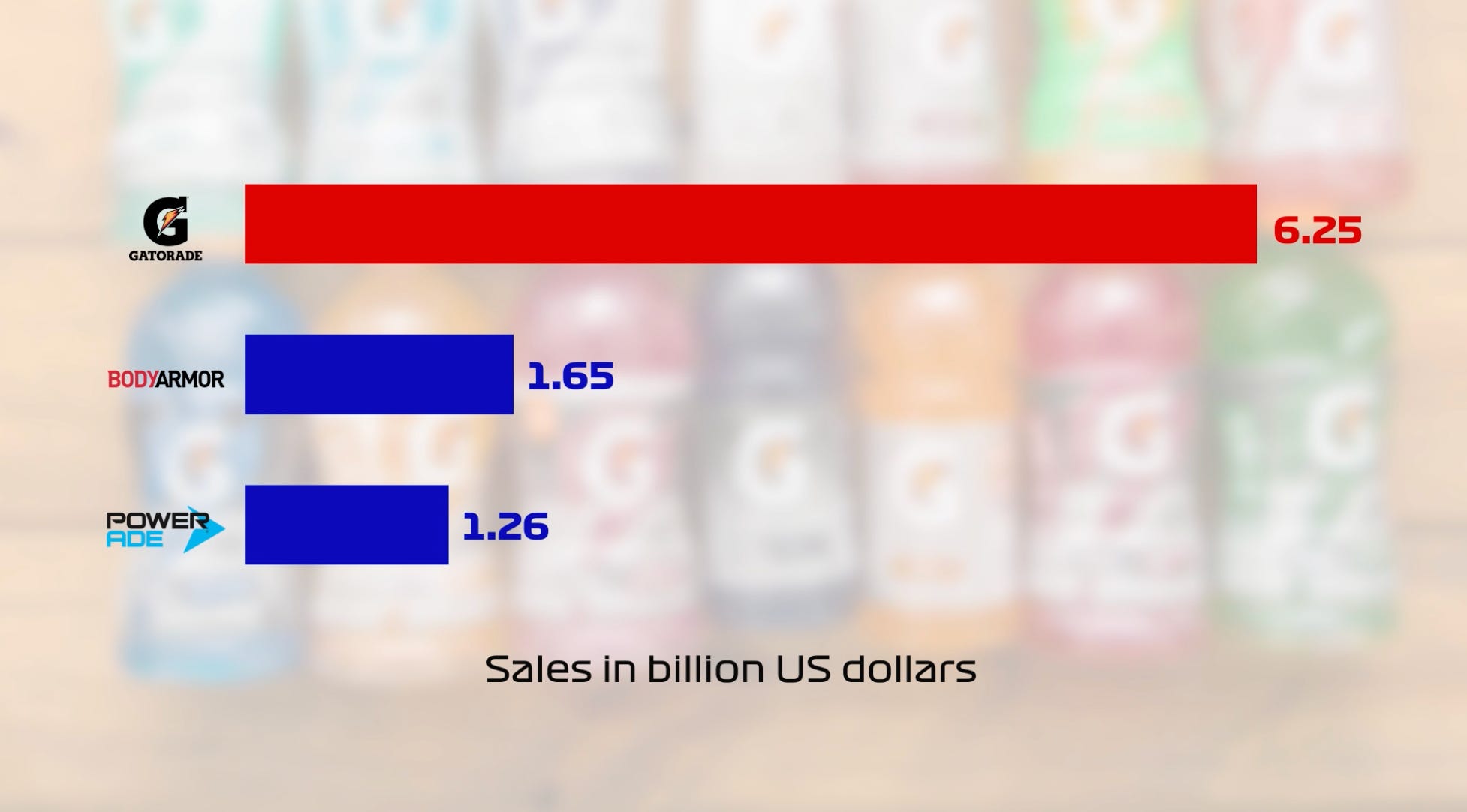

Huddle Up is a 3x weekly newsletter that breaks down the business and money behind sports. If you are not already a subscriber, sign up and join 92,000+ others who receive it directly in their inbox each week. Today’s Newsletter Is Brought To You By Goldin!The world’s top 500 sports cards have an ROI of 855% over the last 15 years, compared to just 175% for the S&P 500 — and there is no better place to start or build your collectible portfolio than Goldin. Goldin is the leading and most trusted destination for some of the most significant pieces of sports and pop culture collectibles. Their marketplace is open 24/7, they have weekly auctions starting at just $5, and there is something for every collector. And here’s the best part: Goldin is offering No Marketplace Fees for items sold up to $10k. So vault and list your items on Goldin’s Marketplace now to enjoy this limited-time offer. I’m a big fan, and I think you will be too. Friends, Gatorade is one of the world’s most popular drinks. The company sells $12,000 of its product every minute and currently owns ~75% of the U.S. sports drink market. Gatorade also sponsors some of the world’s most popular sports leagues — like the NFL, NBA, and MLB — and virtually every big-name athlete has endorsed the brand over the last 60 years, including Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, and Lionel Messi. But the biggest winner behind Gatorade’s success isn’t an athlete at all — it’s a group of four scientists that invented the product in 1965 and made billions in royalties. The Gatorade story has everything — from invention and entrepreneurship to power struggles, royalty deals, and even several lawsuits. So here’s everything you need to know about the fascinating, multi-billion-dollar business behind Gatorade. The Gatorade story starts in the Summer of 1965. The University of Florida football team was losing games left and right, and players were constantly complaining about the hot Florida sun. You see, back in the day, football players typically weren’t allowed to drink water during practice and games. Coaches thought it would make them slow and sluggish, so outside of the occasional salt tablet and gulp of water, no hydration was allowed. This caused players to become severely dehydrated, and it was clearly impacting their performance on the field. So Florida football coach Ray Graves went to the school’s laboratory and asked a group of scientists to come up with a solution. The scientists read up on the thermodynamic physiology of exercise and discovered that players were losing key electrolytes and body fluids as they sweated in the heat. But to prove this thesis and find a solution, the scientists asked Florida head coach Ray Graves if they could study the 1965 football team. And coach Graves agreed, although he only allowed the freshman players to participate in the study. The scientist then started conducting a variety of different tests. They squeezed sweat out from used jerseys after each practice. They took blood and urine samples from each player to measure blood volume, salt and sugar levels, and lipid levels. And they noticed players were losing an average of 260 fluid ounces throughout a 2-hour practice. That’s about 16 pounds in fluids, and the results shocked everyone. “The evidence was clear,” according to Florida lab technician Loren Roby. “At a time when it was common practice to give players salt tablets and not let them drink water for fear of cramping, the players were sweating away massive amounts of fluid and electrolytes, and burning the carbohydrates that gave them energy.” So the group of four University of Florida scientists got to work and tried to come up with a solution. Dr. James Robert Cade led the group, and it included his team of researchers: Doctors H. James Free, Dana Shires, and Alejandro de Quesada. The scientists started by trying to make a drink that replicated sweat. But the first iteration was so bad that the scientists threw up after drinking it. “The taste was horrible, says Lab technician Loren Roby. “Some players spat it out, and others vomited. They described it as tasting like urine or toilet bowl cleaner.” So the scientists kept iterating from there and eventually concocted a formula that contained water, sodium, potassium, and phosphate. This tasted slightly better than the previous version, but the players still thought it tasted like sweat. So lemon juice, orange, and sugar were added, and the first version of Gatorade was born. And the results were immediately clear. The freshman team beat the Varsity B team after drinking Gatorade at halftime of a scrimmage. And within weeks, coach Graves had the entire University of Florida football team drinking Gatorade. And the team started to win — they beat heavily favored schools, even in the hot Florida heat, and quickly became known as a “second-half team” that would outlast its opponents after drinking Gatorade at halftime. And that continued into 1966 when Florida won the Orange Bowl with a 9-2 record, beating Georgia Tech 27-12. Georgia Tech head coach Bobby Dodd even blamed his team’s loss on Gatorade, saying, “We didn’t have Gatorade. . . . That made the difference.” And that’s when word started to spread nationwide. Football teams at the University of Richmond and Miami of Ohio were the first to order Gatorade outside of the state, and it soon became a product that teams felt was necessary to win football games. And just like that, the sports drink category was born. But still, there was a bigger problem brewing under the surface. Gatorade was becoming so popular that schools throughout the country wanted to order the drink, but the scientist didn’t know how to fulfill orders or ship product, and they had no interest in running a business. So the four scientists approached the University of Florida in 1966 with an idea. They offered to sell the entire Gatorade product to the University for $10,000 in cash — or an inflation-adjusted $100,000 today — but the school still declined. And this is when everything took a turn. Two scientists who developed the Gatorade product — Dana Shires and Alejandro de Quesada — left Florida and accepted jobs as assistant professors at the Indiana University School of Medicine. They then met executives from an Indianapolis-based canned bean company called Stokely-Van Camp at a Christmas party in 1966, and the group started talking about Gatorade. The Stokely-Van Camp executives were interested in the product and asked to be sent samples. And after trying batches of lemon-lime, orange, and grape flavors, they reached out and wanted to turn Gatorade into a bigger business. So the four scientists that created Gatorade hired a lawyer to draft the documents, and a deal was done within weeks. The scientists initially wanted to sell the entire company for $1 million, but Stokely-Van Camp was unsure of the demand and decided to pay the scientists $30,000 in cash and a 5-cent-per-gallon royalty in perpetuity. And just like that, the Gatorade sale was complete. The four scientists worked with a lawyer to set up The Gatorade Trust to collect royalty payments, and Stokely-Van Camp started selling Gatorade for 29 cents per quart during the Summer of 1967. Stokely-Van Camp initially put Gatorade in the same 32-ounce cans it used for pork and beans. But the cans rusted from the inside while they sat on grocery store shelves, which caused the Gatorade to leak out of the can and drip on the floor. So the company pivoted just a few months later and put Gatorade in glass quart jars. They took inspiration from the famous Wheaties slogan, calling Gatorade the “beverage of champions” — and sales started to take off nationwide. But with sales increasing and Gatorade quickly becoming a national success, the University of Florida came calling. The school claimed that their labs, football players, and even mascot were used in the formation of the product and argued that they should be entitled to all past, present, and future royalties from the Gatorade brand. “They told me Gatorade belonged to them, and all the royalties were theirs,” Doctor Robert Cade wrote in his autobiography. “I told them to go to hell. So they sued us.” The University of Florida then filed a lawsuit against The Gatorade Trust — but there were a few problems with their case. For example, Doctor Robert Cade and his scientists were funded by the National Department of Health Grants, not the University of Florida. And perhaps even more significant, Doctor Robert Cade had somehow never signed the school’s standard invention agreement, which would have automatically assigned about 75% of the earnings from a deal back to the University of Florida. So after a few months of back and forth, The Gatorade Trust settled with the University of Florida in 1972. The scientists agreed to give 20% of all Gatorade royalties to the University of Florida in perpetuity and kept 80% for themselves. Stokely-Van Camp was then acquired by Quaker Oats Co. for $230 million just a few years later, and this is when Gatorade really started to become a national success. The company paid $25,000 to become the official sports drink of the NFL in 1977 and signed a similar deal with the NBA in 1984. Gatorade also signed Michael Jordan to a 10-year, $13.5 million deal as the company’s first and only endorser and followed it up with the iconic “Be Like Mike” ad campaign, which only cost $10,000 to produce. And the late 1990s were even better for Gatorade. The company was now selling its product in 45 countries. They were doing more than $300 million in annual sales, and the business was growing at an unprecedented 20% year-over-year. This caused PepsiCo to take notice, and the food and beverage conglomerate acquired Quaker Oats Co. for $13.4 billion in 2001. Quaker Oats had a small cereal and snack food division at the time — but PepsiCo saw Gatorade as the business’s crown jewel. And they have invested heavily in the brand over the last two decades. Gatorade now has 22 different flavors and does more than $6.25 billion in annual sales, which is 2x more than competitors BodyArmour and Powerade combined. Gatorade has also expanded beyond its original “Thirst Quencher” product. They have added healthier options like Gatorade Fit and Gatorade Zero. They recently released a Sweat Patch that wirelessly connects to your phone to track workouts, and they are now looking to steal market share from brands like Red Bull and Monster with the launch of their new energy drink, Fast Twitch. And as I said before, no one has benefitted more from the growth of Gatorade than the four scientists that created it at the University of Florida nearly 60 years ago. Brand acquisitions have caused their royalty deal to change slightly over the last few decades, but The Gatorade Trust still collects a royalty between 1.9% and 3.6% depending on annual Gatorade Sales. This has resulted in more than $1 billion in royalty payments being sent to the four scientists that created Gatorade, and the University of Florida has made more than $200 million in royalties themselves. Now, that’s not bad for a product they never intended to sell. If you enjoyed this breakdown, please consider sharing it with your friends. My team and I work hard to create high-quality content, and every new subscriber helps. I hope everyone has a great day. We’ll talk on Wednesday. Interested in advertising with Huddle Up? Email me. Your feedback helps me improve Huddle Up. How did you like today’s post? Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad Extra Credit: Formula 1 Cars Become Digital BillboardsThe McLaren Formula 1 team has introduced digital advertising technology on its car this season. The car has two display panels near the driver’s cockpit, and E-Ink technology allows McLaren to rotate sponsors every 45 seconds throughout the race. This is the first-time digital advertising has been used in F1, and it’ll be interesting to see if McLaren eventually applies dynamic pricing. For example, I bet brands would be willing to pay more based on the car’s position (think: podium, pit stops, TV time).

Joe Pompliano @JoePompliano

McLaren’s F1 team has 40+ sponsors. So they are introducing kindle technology on the car that allows them to rotate sponsors every 45 seconds throughout the course of a race. The panel weighs just 190g, and they are testing the same tech on helmets.

6:22 PM ∙ Feb 23, 2023

8,118Likes824Retweets

Huddle Up is a 3x weekly newsletter that breaks down the business and money behind sports. If you are not already a subscriber, sign up and join 92,000+ others who receive it directly in their inbox each week.

Read Huddle Up in the app

Listen to posts, join subscriber chats, and never miss an update from Joseph Pompliano.

© 2023 |