The Incredible Logistics Of Formula 1

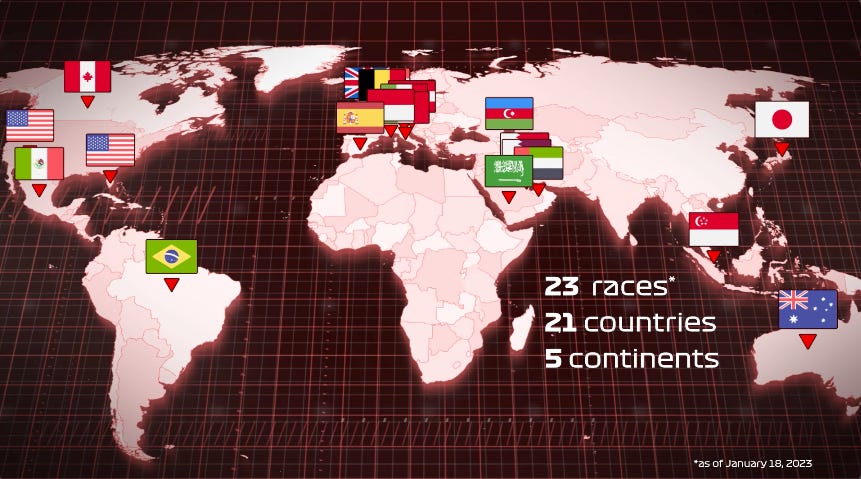

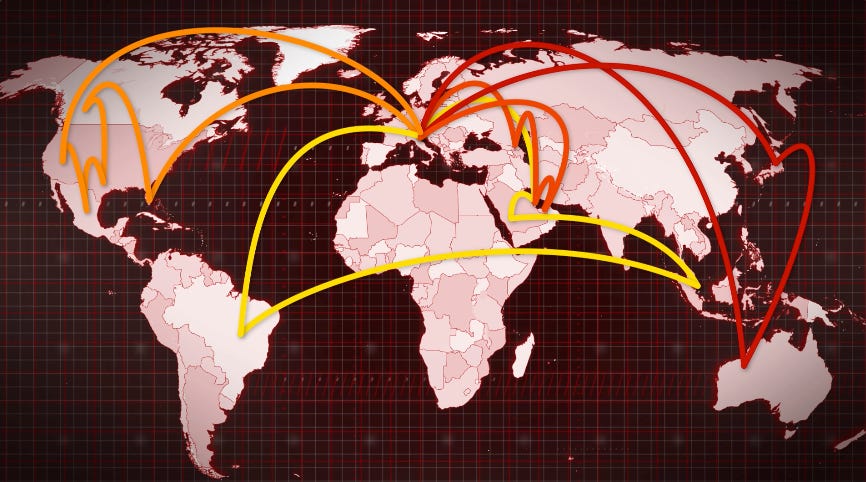

Huddle Up is a 3x weekly newsletter that breaks down the business and money behind sports. Subscribers include investors, professional athletes, team owners, and casual fans. So if you are not already a subscriber, sign up and join 81,000+ others who receive it directly in their inbox each week — it’s free. Today At A Glance:Formula 1 teams spend $145 million annually to build the fastest car, and the 2023 schedule includes 23 races across 20 countries in just 9 months. This makes Formula 1 a logistical nightmare, so today’s email breaks down everything you need to know about the incredible logistics of Formula 1. Enjoy! This newsletter is also available in audio format via Apple and Spotify. Today’s Newsletter Is Brought To You By Sorare!Sorare is one of the fastest-growing companies in sports. Backed by superstar athletes like Lionel Messi, Kylian Mbappé, Rudy Gobert, Aaron Judge, and Serena Williams, they have built blockchain technology that allows fans to collect officially licensed NFT-backed player cards. Sorare, which started in Europe with fantasy football games, recently launched exclusive licensing deals with the MLB/MLBPA and NBA/NBPA to create a custom fantasy game for each sport. The concept is simple: Sorare lets you buy, sell, trade, and earn digital trading cards of your favorite players. But rather than just looking at them as a digital collectible, you can use these trading cards to enter fantasy sports competitions for prizes & rewards. So use my link below for a free limited card — it’s free to get started! Friends, Formula 1 is one of the world’s most interesting sports. The cars weigh nearly 2,000 pounds and reach top speeds of more than 200 miles per hour. Drivers are paid up to $40 million annually and experience nearly the same g-force as an astronaut during takeoff. And teams like Ferrari, Mercedes, and Red Bull employ thousands of people and spend $145 million annually to build the fastest car. This exciting nature of Formula 1 has turned it into one of the world’s most popular sports. Hundreds of thousands of people show up to each race, and another 70 million watch from the comfort of their homes. That’s Super Bowl-level viewership — but it’s every single weekend, not just once a year. Drivers like Lewis Hamilton, Max Verstappen, and Charles Leclerc have become legitimate celebrities with millions of fans. And races are held all over the world, including places like Saudi Arabia, Australia, Miami, Monaco, Italy, Austria, Belgium, Singapore, Japan, Mexico, Brazil, and Qatar. But this also makes Formula 1 a logistical nightmare. For example, the 2023 Formula 1 calendar includes 23 races across 20 countries on 5 continents in just 9 months. Races will be held in 10 different time zones, and drivers will at least spend 240 hours — or ten full days — on flights. Formula 1 teams will transport 1,500 tons of equipment throughout the season and travel more than 75,000 thousand miles in total — enough distance to cover the entire circumference of the earth…three times. They’ll use a combination of trucks, boats, and planes to move cars, engines, and computers. And everything will be planned out 18 months in advance so there are no mistakes. But how exactly do they do it? How much does it cost? And what happens if they make a mistake? Here’s everything you need to know about the incredible logistics of Formula 1. OverviewFirst, it’s essential to understand how Formula 1 works geographically. All ten Formula 1 teams have their own headquarters. This is a physical building that is commonly referred to as a factory, and it’s where the cars are designed, developed, and manufactured. Nearly all F1 factories have a wind tunnel for testing and a simulator to help drivers prepare for each race. Hundreds of employees work in these buildings year-round, and it’s where you’ll find everyone during the week — from sales and marketing teams to engineers and the drivers themselves. But these factories aren’t all located in the same place. For example, Mercedes, Red Bull, McLaren, Aston Martin, Alpine, and Williams are in the United Kingdom, Ferrari, Haas, and AlphaTauri are in Italy, and Alfa Romeo is located in Switzerland. This requires each team to come up with its own custom logistics plan. Teams will start working with F1’s logistical partner DHL up to 18 months before each race. DHL has been working with F1 for nearly 40 years, and they have a team of 35 dedicated specialists that travel to every race to oversee transport, setup, breakdown, and packing. But the simplest way to explain Formula 1 logistics is by breaking the season-long calendar into two parts: European races and flyaway races. European RacesEuropean races are pretty self-explanatory — these are races that take place in Europe, like Zandvoort, Silverstone, Monaco, Monza, Spa, and others. These races are much easier and cheaper logistically because everything is transported by trucks rather than planes and boats. The transportation trucks include refrigerators, exercise equipment, TVs, food, and beds, and they carry everything — from chairs and tables to engines, computers, and cars. Teams arrive about a week before the circuit is open to ticket holders, and 27 trucks are unloaded over 5 days to ensure the entire paddock is finished by Wednesday. And since trucking is so much cheaper than planes, teams will transport entire buildings to construct at European races. These structures are called motorhomes. They serve as temporary headquarters at each race and have everything needed to manage and feed entire F1 teams. Take Red Bull Racing, for example. Their motorhome is three stories tall and more than 13,000 square feet. It has offices, an outdoor deck, a private chef, and an espresso bar. It takes 25 crew members 36 hours to assemble it, but just one day to take it down. And when it comes to Monaco — Red Bull doesn’t mess around. They take the 13,000-square-foot motorhome apart, transport it to Imperia on the Italian Riviera, spend 32 hours reassembling it on a barge, and tow it 20 nautical miles down the Mediterranean coast. The 100-ft tall structure floats in the Monaco harbor all week, and the pool frequently gets used after victories. But the most challenging part of the European F1 calendar is back-to-back races. These races take place on two consecutive weekends, and transportation crews are given just three full days to break down, travel, and rebuild their base at the next race location. For example, let’s look at this year’s Hungarian Grand Prix and Belgian Grand Prix. These two races will be held just seven days apart, and the schedule will look something like this: Crews will immediately start packing things up while the FIA — F1’s governing body — completes their post-race inspection. The teams will work all through the night and eventually finish packing around 6 am the next morning. And that’s when each team’s truck drivers head out. Teams usually place 2 to 3 drivers in each truck, and they take shifts driving so that they only have to stop for gas. The drive covers about 1,300 kilometers and takes 12 hours, so they’ll arrive at some point on Monday night if everything goes as planned. The remaining 50+ crew members will meet them at the track and immediately start unloading. They’ll have to rebuild everything exactly how it was, and they only have two days to do it. This means members of the logistics crew often work 15-hour shifts, and team chefs feed them with minimal setup to ensure they’re fueled and can keep working. And it’s not like this happens just once a year — there are seven back-to-back races in 2023 alone. Teams will cover about 15,000 miles over five months during the European season, and transportation crews will spend about two months on the road physically away from home. But that’s the *easy* part of the Formula 1 season, at least logistically. Flyaway RacesFlyaway races are an entirely different logistical beast. The 2023 season includes races in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Miami, Canada, Mexico, Qatar, Brazil, Las Vegas, and Abu Dhabi, and teams will start planning for these races months in advance. For example, three months before the Formula 1 season even starts, all ten race teams pack five kits of shipping containers. Of course, wealthy teams like Red Bull, Mercedes, and Ferrari might use a few more containers, but a typical kit includes three 40-foot shipping containers. These shipping containers are packed with all non-critical equipment for race weekend, including jacks, trolleys, chairs, tables, kitchen equipment, and more. And they travel by boat in a leapfrog pattern from each flyaway race destination to the next. So after each race is finished, the kit is repacked and shipped to the next flyaway race that doesn’t have a kit. Let’s use the 2023 season as an example:

These kits will then return to the team’s home base for the winter after the season ends. Here’s an illustration of how this “leapfrog pattern” will look in 2023: This five-kit approach gives teams a bit more leeway when it comes to time, and they save a ton of money by shipping the containers on boats rather than airplanes. But the most challenging part of the Formula 1 season is undoubtedly back-to-back flyaway races. These are two races, on back-to-back weekends, that are often hundreds (or thousands) of miles apart. Take Las Vegas and Abu Dhabi. These races are just one week apart, but teams will be required to travel more than 8,200 miles. They’ll be on a plane for nearly 20 hours and have to deal with an 11-hour time difference when they arrive. The Las Vegas Grand Prix is on a Saturday night, so pack-up will begin during the race. Teams will start by loading up spare parts that can’t be used once the race has started, like additional engines, and the rest of the pack-up begins just 15 minutes after the race ends. The most important items are loaded onto priority pallets and then driven directly to the airport just hours after the race. Pallets from all ten teams are then loaded onto five Boeing 777s for an early flight on Sunday morning — these planes are chartered by Formula 1, but each team pays for the space they use. The rest of the pallets are then loaded onto additional airplanes within 4 to 6 hours, and each team’s staff starts their travel the day after the race. Lower-level staff fly on commercial flights, while higher-profile drivers often fly private. The cargo planes will land in Abu Dhabi on Monday, and after going through customs, they’ll be driven to the racetrack for the assembly crew to start setting everything up. But there is one important stipulation: No team can touch their freight until every team’s freight arrives. This is done to ensure that no team gets a head start and everyone ends up on an equal playing field. The assembly crews will then have less than 48 hours to set everything up before drivers and team principals start to arrive. This process begins with basic things, like installing custom wall paneling in the garage. But it ends with complex tasks, like setting up an electrical system for radio and computer equipment. And these races are equally as difficult for drivers, albeit in a slightly different way. Because there are so many time zone changes that teams deal with — especially with back-to-back races — Formula 1 drivers are constantly fighting jet lag. Faith Fisher-Atack, the physio for Hass, told the New York Times that “there is a clear correlation between jet lag and then having poor performance, and if you equate that to what [they] have to do on the car, there’s a clear consequence.” So drivers work with their trainers in several ways to combat this jet lag. Most of them try to arrive several days early to a race destination when time permits — but Rupert Manwaring, the physio for Ferrari driver Carlos Sainz, told the New York Times that “there is no firm rule for shifting to a new time zone.” Manwaring says, “The simple rule is for every hour difference, you need a day to adapt. If it is a nine-hour time difference, we’ll try and arrive that number of days in advance, but that can be a challenge over the course of a season, as being at home is important outside of races. We are dealing with humans, not robots.” These jet lag symptoms typically last between three to five days, and each driver has their own unique way of dealing with it. Some drivers limit light exposure so that their bodies can adapt quicker, while others wake up early and complete a light workout to adjust — but virtually everyone uses caffeine. “You take it little and often, rather than in big chunks,” Manwaring says. “We’d not use it immediately after waking, and not beyond 1 p.m., because caffeine has quite a long half-life and can stay in the body for up to 10 hours, so you have to be careful about the night ahead.” And for night races like the Singapore Grand Prix, teams will shift their entire schedule from 1 pm to 6 am, avoiding housekeeping at their hotels and keeping rooms dark to avoid morning light. Ultimately, the Formula 1 season is a mental and physical grind. The season runs for 9 out of the 12 months in a single calendar year, and employees often spend weeks away from their families at a time. Each team spends thousands of hours and millions of dollars annually on logistics, and the difference between winning and losing can come down to just milliseconds. But I guess that’s all part of the reason why Formula 1 is one of the world’s most popular sports. If you enjoyed this breakdown, please share it with your friends. My team and I work hard to consistently create quality content, and every new subscriber helps. Thanks! I hope everyone has a great weekend. We’ll talk on Monday. Enjoy this content? Subscribe to my YouTube channel. Your feedback helps me improve Huddle Up. How did you like today’s post? Loved | Great | Good | Meh | Bad Huddle Up is a 3x weekly newsletter that breaks down the business and money behind sports. Subscribers include investors, professional athletes, team owners, and casual fans. So if you are not already a subscriber, sign up and join 81,000+ others who receive it directly in their inbox each week — it’s free.

Read Huddle Up in the app

Listen to posts, join subscriber chats, and never miss an update from Joseph Pompliano.

© 2023 |