How Sports Team Owners Made Millions Off Taylor Swift’s $2 Billion Eras Tour

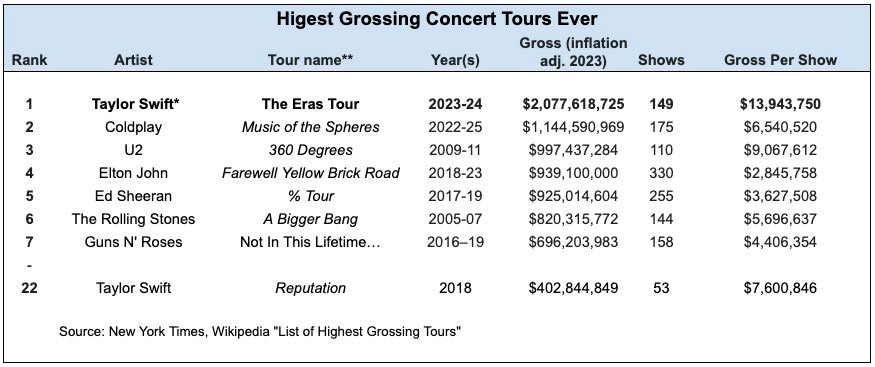

Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour officially ended this weekend in Vancouver, Canada. What began in March 2023 as a 52-show US Tour eventually transformed into an 18-month international juggernaut with 149 shows on five continents. The final numbers are mind-blowing. Each performance lasts 3.5 hours, with Swift playing 44 songs and conducting multiple costume changes. Fans literally shook the ground so hard in Seattle that it registered on a seismometer as equivalent to a 2.3 magnitude earthquake, and notable attendees throughout the tour included everyone from Tom Brady and JJ Watt to Tom Cruise, Bradley Cooper, and Prince William. Rumor has it that 3x Super Bowl Champion Travis Kelce also made it to a few shows. Jokes aside, the economic impact of Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour is historic and still being felt today. Cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, London, and Sydney collectively generated hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue. The Eras Tour is also the first concert tour in history to surpass $2 billion in total revenue, helping Taylor Swift become the first billionaire musician in history to make her fortune solely from music.

Even crazier, estimates indicate that the average Eras Tour attendee traveled 338 miles and spent nearly $1,600 on a single show. That includes money spent on tickets, travel, lodging, outfits, merchandise, and food and drinks, and it is similar to what an NFL fan might pay to attend the Super Bowl, with the difference being that the Super Bowl only happens once a year while Taylor Swift played 149 shows over 18 months. In fact, Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour generated so much economic impact that economists have started referring to its impact as “Swiftonomics.” However, while everyone seems to focus on how much local restaurants, bars, and hotels made from each concert, the truth is that few people benefited more than professional sports team owners. The Eras Tour has held concerts in about a dozen sports team-owned stadiums over the last 18 months. This includes several international venues, like Liverpool’s Anfield in the United Kingdom and Real Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu in Spain, and it also includes US-based stadiums like Gillette Stadium in Massachusetts, Hard Rock Stadium in Miami, MetLife Stadium in New Jersey, and SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles. The nightly economics are slightly different on a stadium-by-stadium basis because ticket prices tend to trade at a 20% to 30% premium in the United States. But for the sake of simplicity (and the fact that many international venues are bigger than US stadiums), we’ll apply some generalizations to determine how much each venue made. According to the Wall Street Journal, the average Eras Tour show generated about $10 million in ticket sales. That number was slightly higher for bigger shows ($13 million) and lower for smaller shows ($6 million). However, it stayed pretty consistent throughout the tour because Swift didn’t participate in dynamic pricing, meaning the increase in ticket prices over time was solely due to demand on the secondary market. Swift then must pay out various expenses before we start talking profit. This includes a mix of fixed and variable costs, like labor, transportation, production, staging, and promoter fees. But one of the largest expenses is renting the actual venue. Based on a $10 million show, each stadium might charge $2 million to $3 million per night. This is fantastic for a venue that would otherwise be empty, but it gets even better when you remember that some stadiums hosted several consecutive nights. For example, Swift performed at Anfield in Liverpool for three consecutive nights in June, and she did the same thing at Gillette Stadium, Hard Rock Stadium, and MetLife Stadium. Rogers Centre in Toronto and SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles got even more fortunate, hosting six shows each throughout the duration of the tour. It’s not just ticket revenue, though. Stadiums also typically get a cut of concession and merchandise revenue. And with the Eras Tour generating about $2 million in nightly merchandise sales, these venues made a ton of money off Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour. In total, it’s estimated that each stadium made about $3 million to $4 million during each show of the Eras Tour. Multiply that by the number of nights each venue hosted a show, and we are talking $6 million to $8 million in revenue on the low end (two nights) to $18 million to $24 million in revenue on the high end (six nights). Taylor Swift is obviously an outlier. Only a handful of artists in the world could sell out an NFL stadium six nights in one week, and Swift even produced a movie version of The Eras Tour for fans who couldn’t attend in person. That movie was released in nearly 4,000 theaters worldwide and has now done over $260 million in box office revenue, making it the highest-grossing concert film of all time. But this is also why owning your own venue in professional sports is advantageous. Take SoFi Stadium, for instance. The $5 billion privately-funded venue hosts weekly NFL games for its home teams, the Los Angeles Rams and Chargers. But since the venue is 1) spectacular and 2) located in LA, it also gets contracted for a bunch of other special events, like the CFP National Championship game, Wrestlemania, and 19 concerts last year alone, including six with Taylor Swift and three with Beyonce. Not all of this money is profit, of course. But these events will collectively generate hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue for billionaire owner Stan Kroenke’s portfolio of assets, which includes the Los Angeles Rams (NFL), Denver Nuggets (NBA), Colorado Avalanche (NHL), Colorado Rapids (MLS), and Arsenal (EPL). The results are more impressive for small market teams, like second-division Bundesliga clubs, who operate annual payrolls of $25 million to $50 million yet generated roughly $10 million in revenue each from Taylor Swift concerts in 2024. Many people will look at these numbers and say building financial models based on Taylor Swift concerts is unrealistic. And they aren’t wrong — this was the highest-grossing concert tour of all time, and there is no certainty that it will happen again. However, with media rights facing an uncertain future, the smartest owners in professional sports have started to position their sports teams as real estate assets. This includes increasingly popular mixed-use developments, like the Battery in Atlanta or the Deer District in Milwaukee. But it also includes the venues themselves. The Buffalo Bills can get away with building an open-air stadium because the city’s infrastructure is too small to land a Super Bowl or Final Four anyway. But most big-city professional sports teams have at least looked into domes because enclosed roofs would allow them to host premier concerts and sporting events throughout the winter. Many of these venues are still funded by taxpayers. But even if the individual sports team doesn’t technically own the venue, they almost always try to find a way to pay some operating costs so that they can participate in the upside of ancillary events, too. If you enjoyed this breakdown, share it with your friends. Join my sports business community on Microsoft Teams. Huddle Up is a 3x weekly newsletter that breaks down the business and money behind sports. If you are not a subscriber, sign up and join 125,000+ others who receive it directly in their inbox each week. You’re currently a free subscriber to Huddle Up. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

© 2024 |