Steve Cohen Wants To Spend $8 Billion To Transform Citi Field Into An Entertainment District

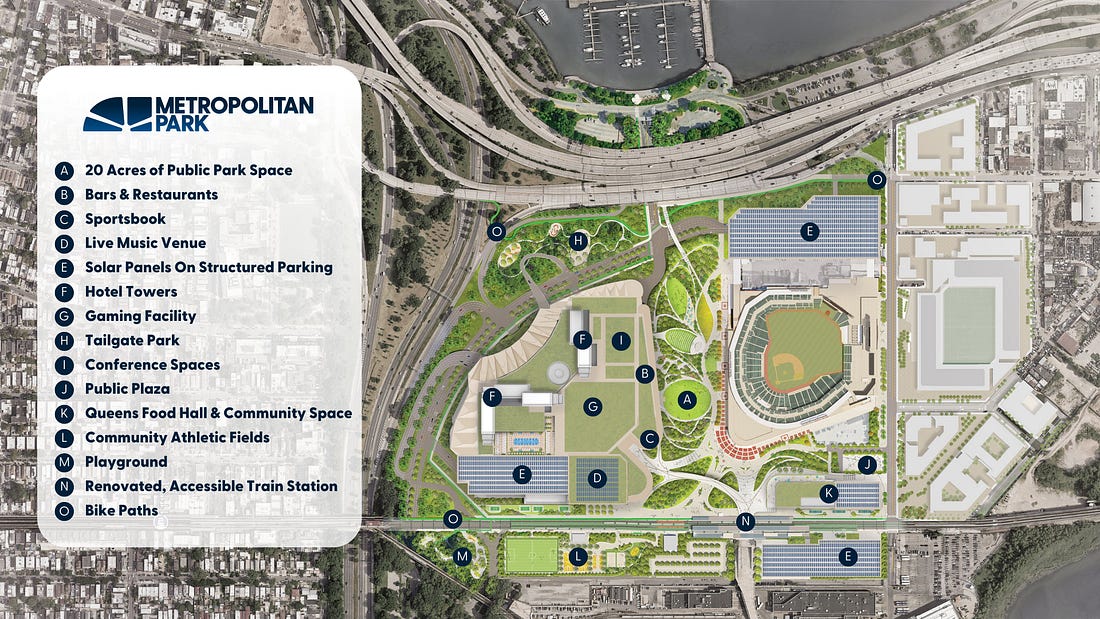

Last month, hundreds of Mets fans gathered at Citi Field in Queens, New York, for the team’s “Amazin’ Day” fan fest. Never one to play it safe, billionaire owner Steve Cohen pulled out all the stops to make sure everyone left with unforgettable memories. Fans took pictures and got autographs from franchise legends like David Wright and Mike Piazza. Cohen gave VIP ticket holders a tour of his owner’s suite behind home plate. You could also visit the team’s museum, take some swings in the same batting cage used by the players, and even throw a few pitches from the bullpen in the tunnel. That’s who Steve Cohen is as an owner. After buying his childhood team for a record $2.4 billion in 2020, the billionaire hedge fund manager has made it clear that he isn’t trying to make money on the Mets; he just wants to have fun and win championships. Maybe that sounds too good to be true, but it’s not. Given Major League Baseball doesn’t have a salary cap, the league office had to rewrite its luxury tax rules in 2020 because Cohen was spending so much more on player contracts than everyone else. Known as “the Cohen Tax,” this new rule added a fourth tier to MLB’s luxury tax system, assigning a 62.5% penalty to any salary exceeding $250 million annually. Cohen’s complete disregard for profit has rubbed some owners the wrong way, but he doesn’t care. In fact, Cohen’s taking it a step further, attempting to follow through on an $8 billion, privately funded project to transform the land surrounding Citi Field. Hidden between the food vendors and memorabilia collections at Amazin’ Day, Mets fans saw a glimpse of Cohen’s vision. Named “Metropolitan Park,” fans were shown a diorama of what Cohen believes the Mets fan experience should eventually look like. While some real estate ideas are so complex that owners can’t explain them without a presentation, Cohen’s plan is simple. He wants to convert 50 acres of asphalt parking lots surrounding Citi Field into a mixed-use development with public parks, hotels, live music venues, bars and restaurants, and, yes, even a casino and sportsbook. Cohen is not asking taxpayers for any money, and nearly all the land earmarked for use is already vacant, meaning no residents or businesses will be displaced. Metropolitan Park is still several steps away from being a reality. Some people don’t want it built, and there is no guarantee it will be built. However, this $8 billion project provides a glimpse into what professional sports teams will look like in the future.

One of the biggest trends in sports business over the last two decades has been the transformation of sports teams into real estate assets. Back in the day, owners relied on ticket sales and concessions. Then, merchandise and sponsorships became more important, eventually giving way to multi-billion-dollar annual media rights deals. This mixed-revenue model is still highly lucrative for some leagues and some owners. However, one thing that many fans don’t realize is that a good percentage of sports teams don’t actually turn a profit each year; they simply wait long enough for the team’s value to increase before cashing out on that equity appreciation. This is where real estate comes into play. Physical infrastructure has some ancillary benefits, but think of real estate in sports as just another revenue-generating line item. The most competent owners in sports understood many years ago that it was essential to maximize a venue’s capacity. This trend started with more seats and nicer luxury suites, helping NBA teams graduate from doing six figures in revenue per home game to $2 million-plus home games today. However, while many think of capacity in terms of how many people you can fit into an arena, stadium, or ballpark, the total number of annual usage days is equally important. If your team isn’t playing, then the venue is empty, so you might as well try to generate revenue from concerts or comedy shows. The only problem with this approach is that most stadiums have a limited design. NBA arenas work pretty well for concerts and other events, but NFL stadiums are often too big. The setup of an MLB stadium provides a poor viewing experience for anything other than baseball, and MLS stadiums are seldom used because there is usually an indoor venue with the same number of seats somewhere nearby in that city. Due to these design limitations, owners started thinking outside the box. Rather than solely trying to maximize revenue inside the venue, they took this theory to the streets. The New England Patriots have stores, restaurants, and a hotel in Patriot Place outside Gillette Stadium. Six million people visit Ballpark Village next door to Busch Stadium in St. Louis each year, and The Battery in Atlanta might be the gold standard. Open 365 days a year with restaurants, bars, hotels, and shops, The Battery in Atlanta will generate $60 million in revenue for the Braves this year. Even better, this money sits outside MLB’s revenue-sharing agreement, so the Braves keep it all to themselves. This is what Steve Cohen wants to replicate in New York. Except, like everything else he does, Cohen wants his project to be bigger, better, and busier than anywhere else. The Metropolitan Park project has a lot of potential. Instead of parking on asphalt lots, Mets fans would have access to the same number of spots in nearby garages. The current plan is estimated to create more than 23,000 permanent and construction jobs, with local residents prioritized over out-of-towners. Cohen is also promising that $1 billion of the proposed $8 billion construction budget will go toward community benefits, which includes renovating the nearby Mets-Willets Point 7 train station. Like any significant real estate project, opinions vary on whether this is a good idea. Proponents say it will create jobs while turning a dead area into a 24/7, 365-day-a-year entertainment destination for sports fans and tourists. Others discuss gentrification and say building more affordable housing units provides more benefits than a casino. Regardless of your position on the issue, Steve Cohen and his partner on the project, Hard Rock International, still need to overcome several hurdles. Cohen has spent the last year sponsoring political conferences to curry favor with local politicians. That’s because he still needs state and city approval for the land designation and the New York Gaming Commission to award him one of just three downstate casino licenses. It’s too early to tell how much financial benefit Cohen would receive from a project like this. There are too many variables. We don’t know the final construction costs, the necessary fee to secure a gaming license, or the required state and local taxes. But don’t be surprised when more projects like this get announced. Steve Cohen is unique because he is far wealthier than most other owners in professional sports and is willing to spend excessive amounts of money without expecting a financial return. Not every owner is like Cohen, though. Some of the best sports owners have already found a way to work with local governments to build similar projects, albeit usually on a smaller scale. Now, the rest are determining how they can do something similar. Mark Cuban has already said that he sold the Dallas Mavericks to the Adelson family because he lacked the expertise to build a resort and casino around the team’s arena in Dallas. But Cuban is not alone. American owners know media rights could soon hit an inflection point and that real estate will be the next best way to grow enterprise value. If you enjoyed this breakdown, share it with your friends. Huddle Up is a 3x weekly newsletter that breaks down the business and money behind sports. If you are not a subscriber, sign up and join 129,000+ others who receive it directly in their inbox each week. You’re currently a free subscriber to Huddle Up. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

© 2025 |